A Lesson

Canvassing for Jackson in Another Century

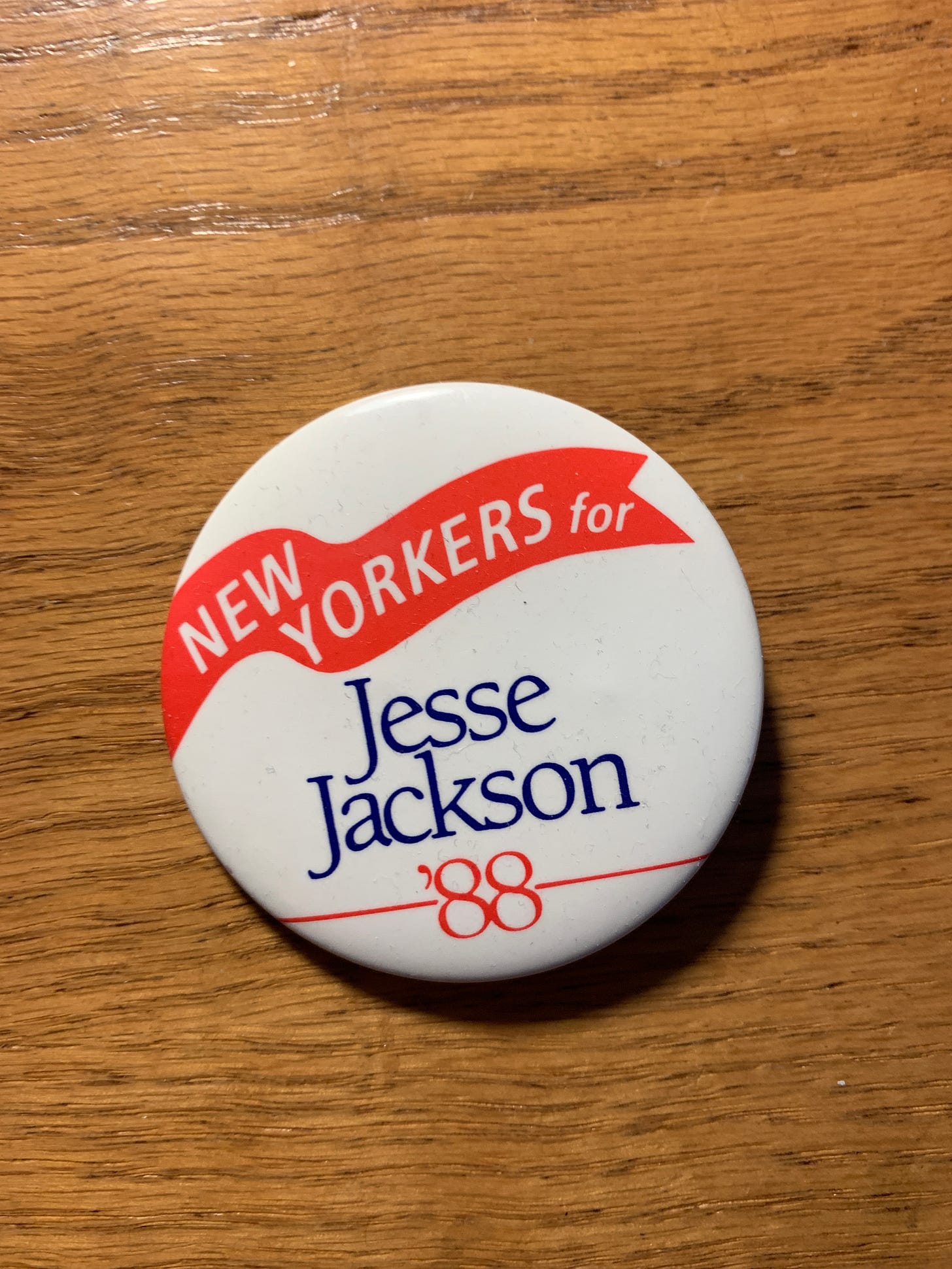

I was 25 when Jesse Jackson ran for President the second time. One year before that, my family and I had moved to Syracuse, New York, where we found a more progressive and diverse community than what we had left behind in Pennsylvania.

That spring, a friend and I both signed up to help with the Jackson campaign. (I believe the first candidate I was drawn to that year was Missouri Representative Dick Gephardt, who withdrew in March; I might also have been interested in Arizona Governor Bruce Babbitt, who withdrew in February.) After attending at least one strategy meeting with local Jackson organizers, my friend and I went together to canvass for Jackson in a working-class Black neighborhood on the East Side. (Redlining had established (or rather, insisted on) this as a Black neighborhood decades before.)

I have vivid memories of sitting behind Jackson on stage (and minding his glass of water) when he came to speak at the Syracuse War Memorial—where my wanderings days ahead of the event led me to point the Secret Service detail to a more secure entrance path for Jackson (this feels like an invented detail, even as I recall it)—but the most profound experience for me came in that canvassing.

Arriving together, but then splitting up to cover more ground, my friend and I walked the quiet neighborhood near Lemoyne College, a Jesuit institution. I carried only a clipboard of sheets and wore a light jacket; I didn’t know what to expect. From the first, I saw that I had been seen: Shades parted and curtains were drawn aside to monitor my approach. I felt a revelatory awe at recognizing that I was the possibly threatening outsider. Why was a white guy intruding in the neighborhood?

And then, so often, after people opened their inner doors to see who exactly had rung their doorbell, and after I explained that I was canvassing for Jackson, I received outsized positive responses. We exchanged good wishes, shrugs about the likely outcome, and hopes for a better future. Most significantly in my memory, I had to repeatedly turn down invitations to come inside and have a piece of pie.

I grew up in a very white town where the majority of Black families lived on one block near my elementary school. My high school of over 3,000 students had, in all the years I was there, maybe a half-dozen Black students at most. (I can name all the guys.) The Jackson campaign, with its diverse group of local leaders and its willingness to send me someplace unfamiliar to help “get out the vote,” taught me one of my first lessons about how to be both “other” and ally.

Thanks, Jesse.

This is a cool story that I didn’t know about!